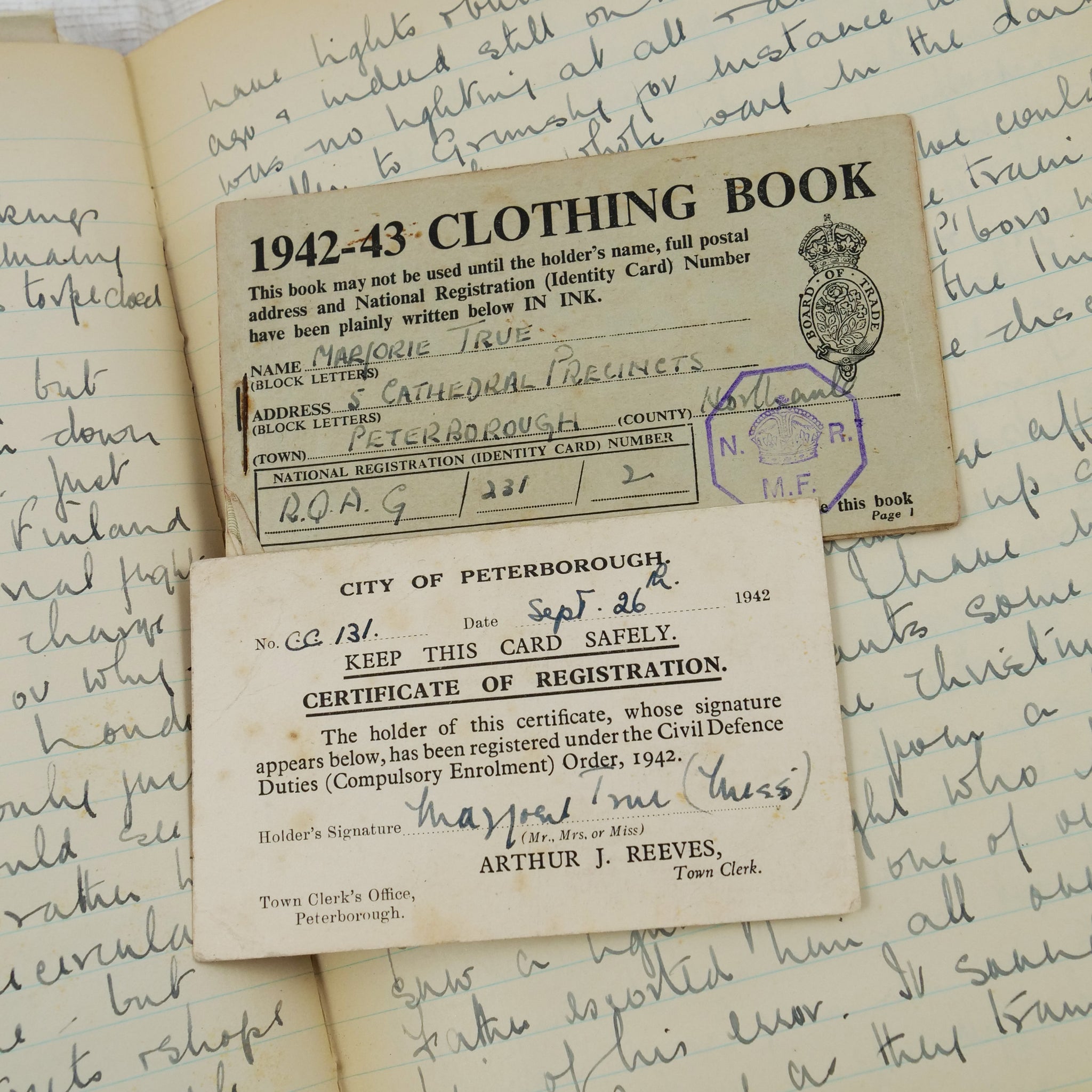

True, Marjorie | Diary of a British Second World War Civil Defence Volunteer: September 1939-October 1941

£2,500.00

-

Content advisory: contains anti-Semitism.

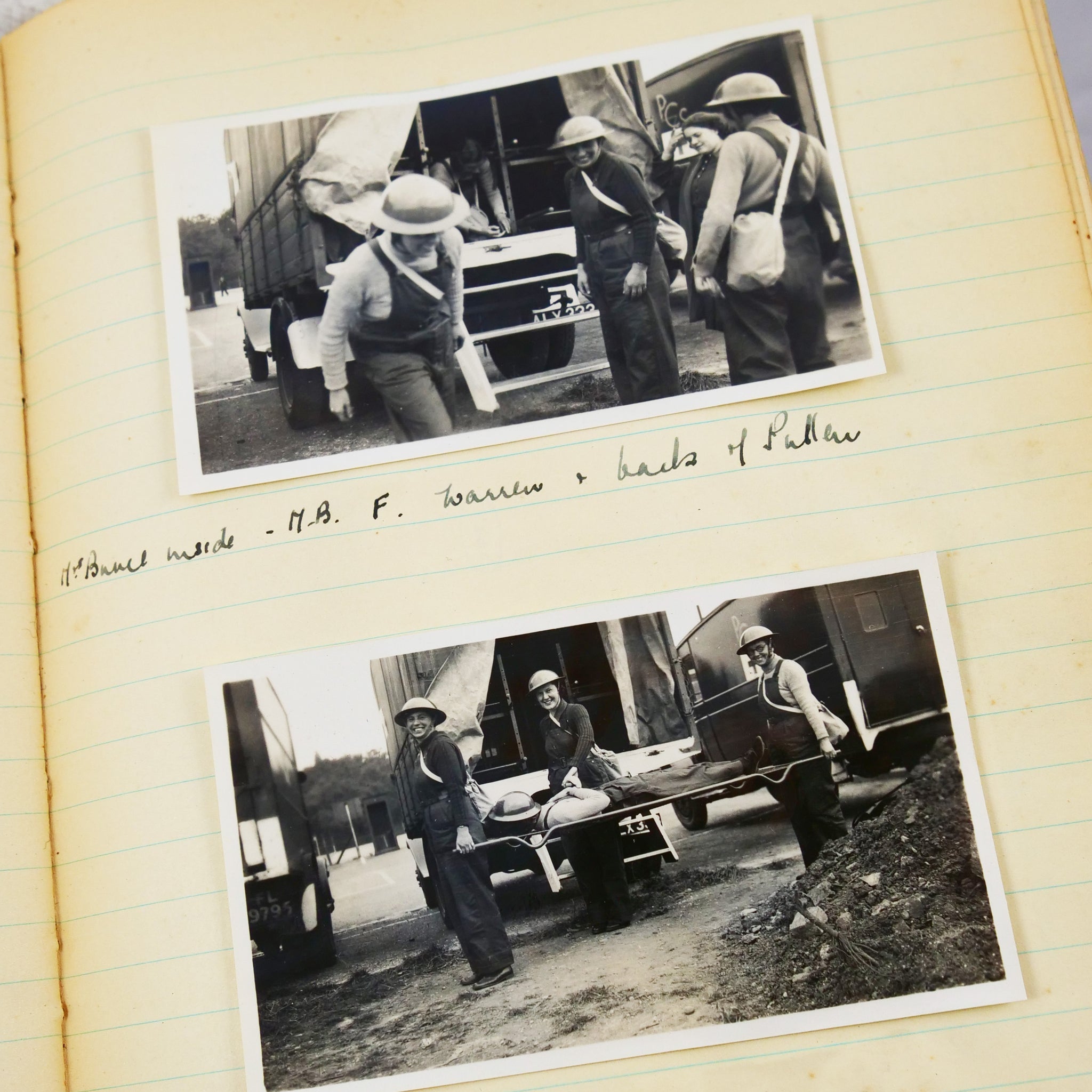

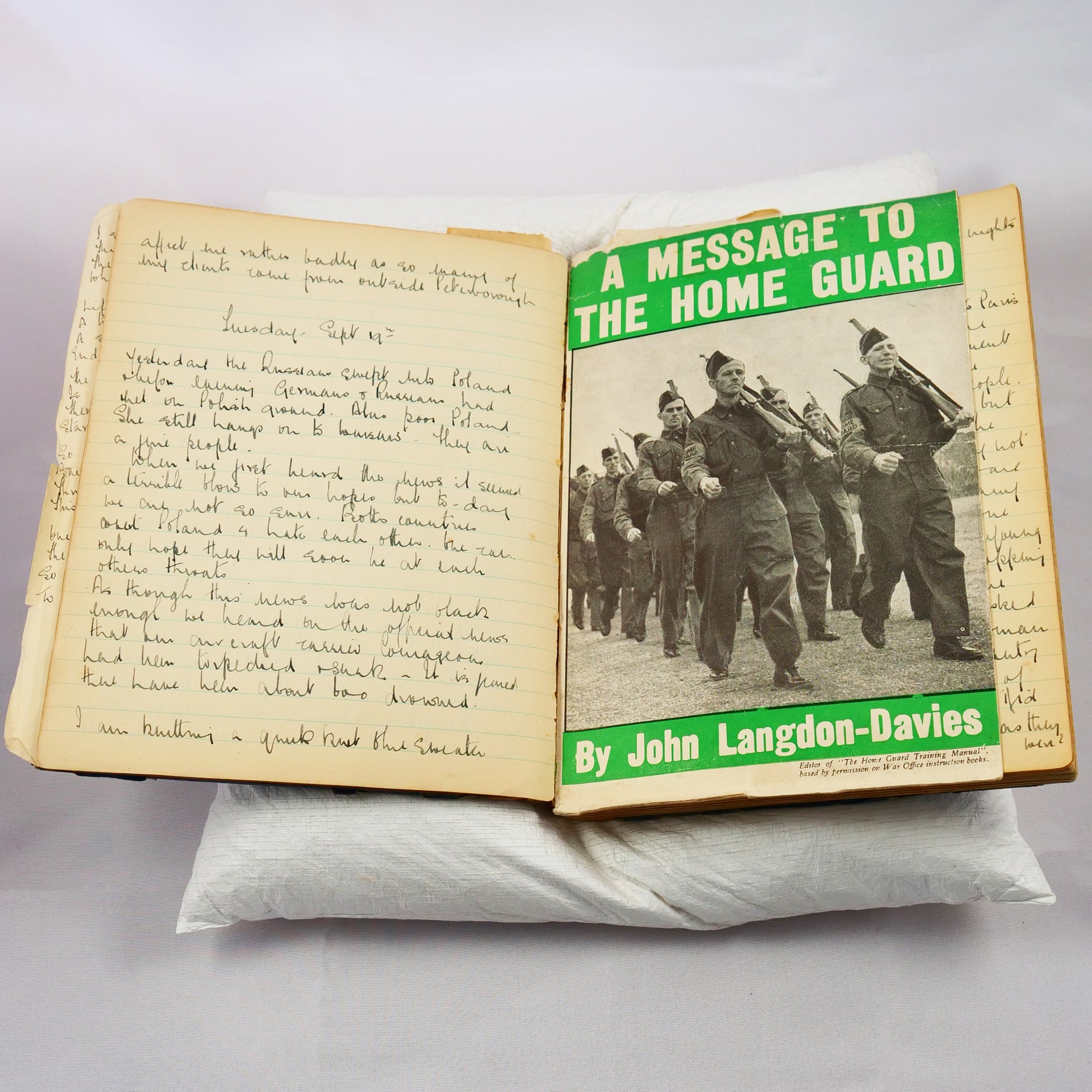

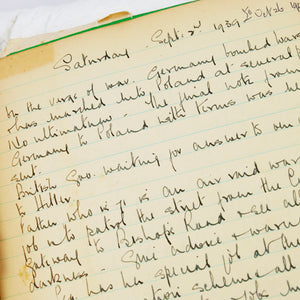

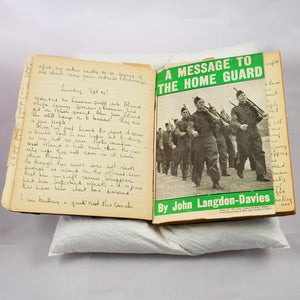

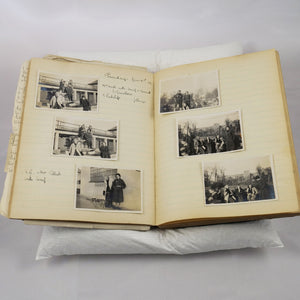

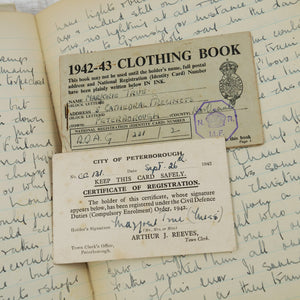

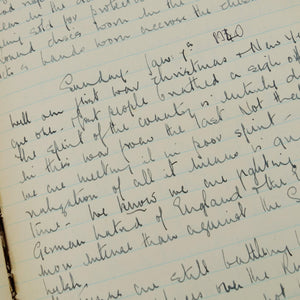

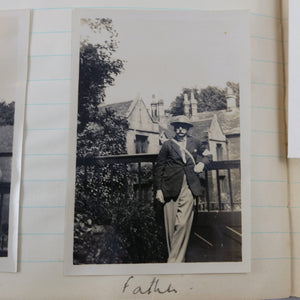

A dense, detailed, and revealing diary chronicling the first two years of the Second World War by Marjorie True of Peterborough’s Cathedral precinct, who was active in the Women’s Voluntary Service. In addition to the eighty-six pages of manuscript text there are sixty-five photographs pasted-in, as well as ephemera (including her clothes ration book and City of Peterborough registration card for Civil Defence Duties) and news clippings, mainly documenting her civil defence work. This diary is of historical importance and would benefit from knowledgeable institutional cataloguing and conservation.True seems to have begun her diary specifically to document the war, with the first entry dated September 2nd, 1939: “On the verge of war. Germany bombed Warsaw & has marched into Poland at several points. No ultimatum — the final note from Germany to Poland with terms was never sent. British Gov. waiting for answer to our ultimatum to Hitler. Father who is 71 is an air raid warden. His job is to patrol the street from the Cathedral gateway to Bishop’s Road & see all is in darkness — give advice & warning... I am an ambulance driver’s attendant which meant being trained in first aid, gas & map reading...”

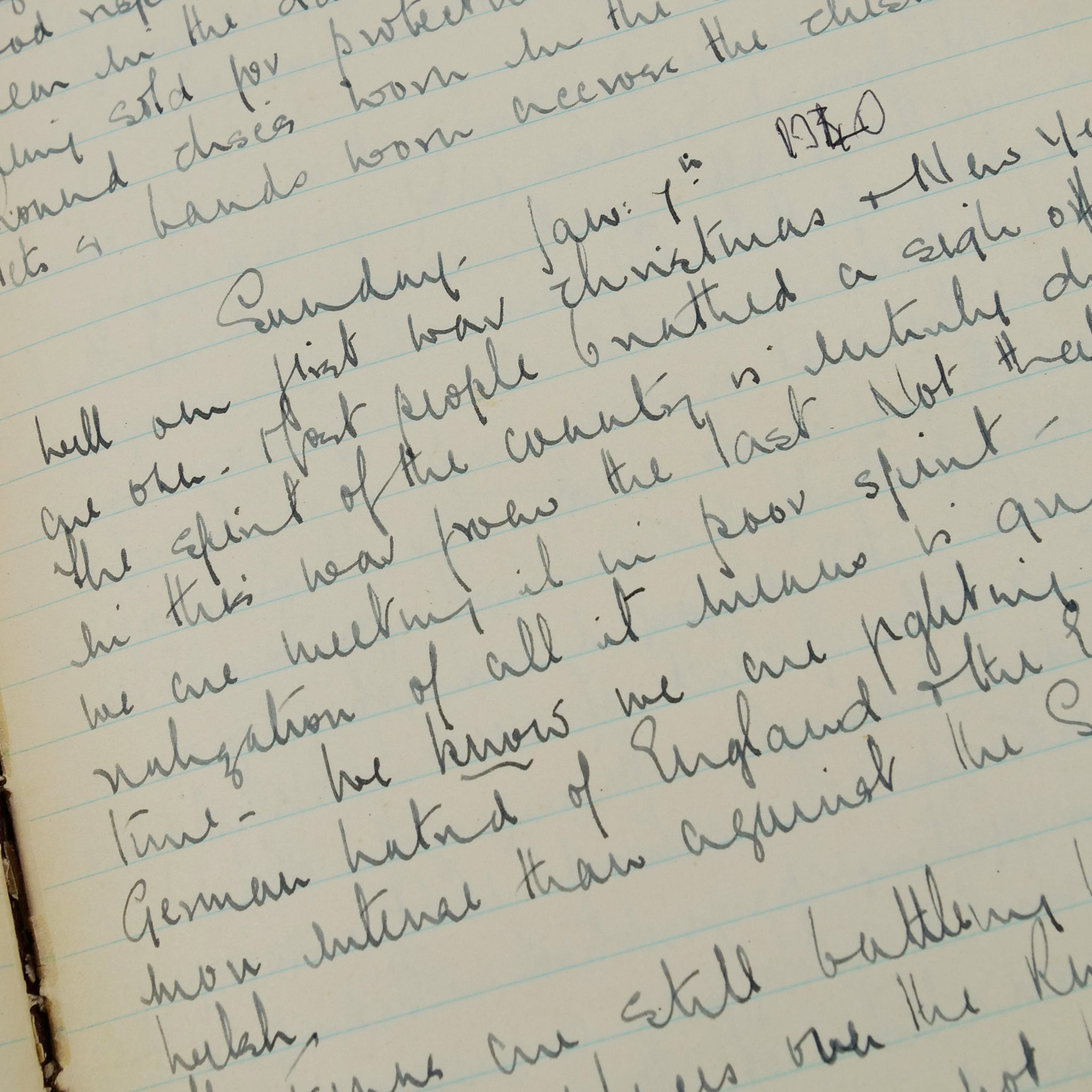

The diary continues in this fashion for the next two years, chronicling international events alongside her voluntary work, local goings-on, private and public sentiment, and rumours. She closely follows the advances of Germany and Russia across the continent, and the efforts made by western European governments and armies as one by one they fell to the Blitzkrieg, often commenting on the fortitude of the Europeans.

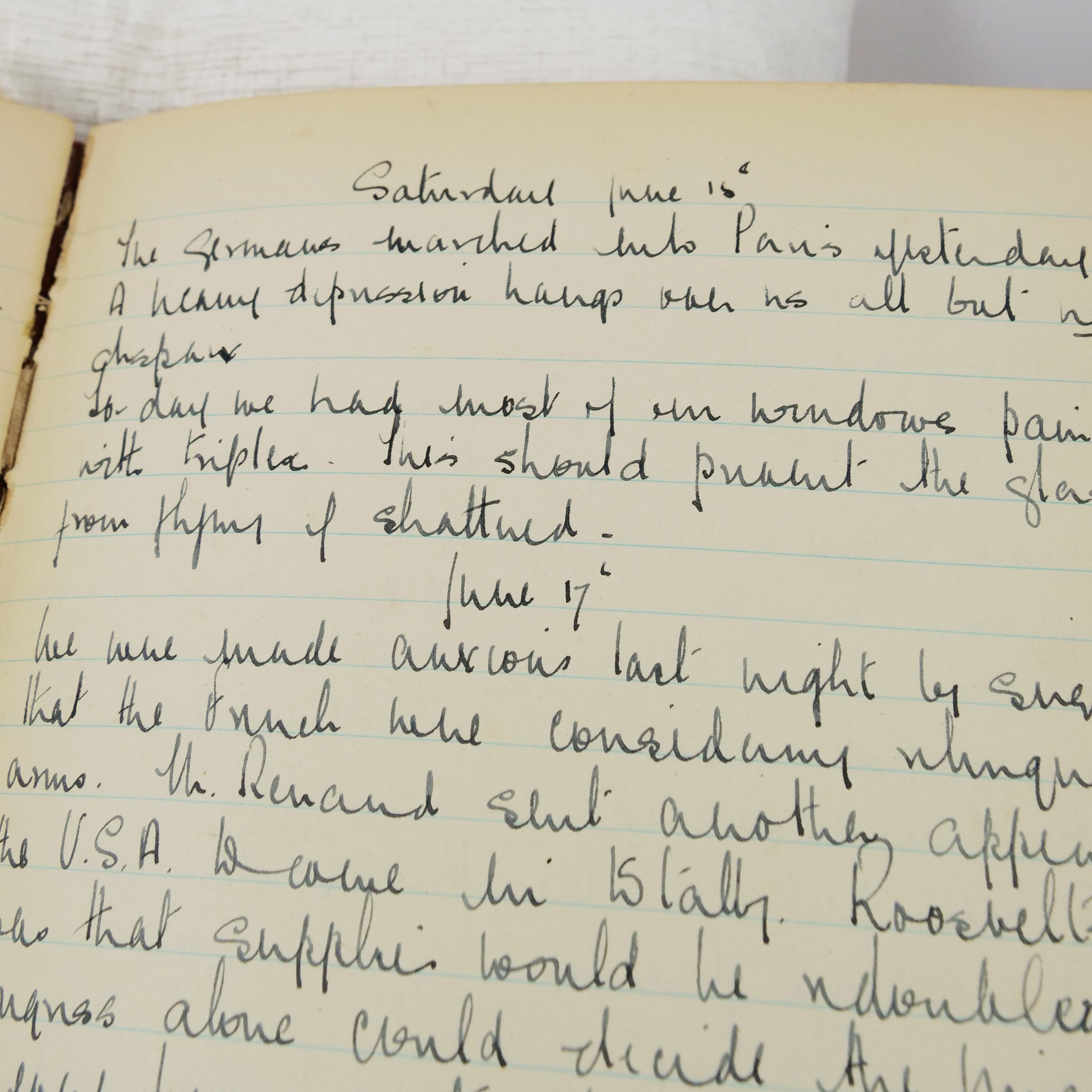

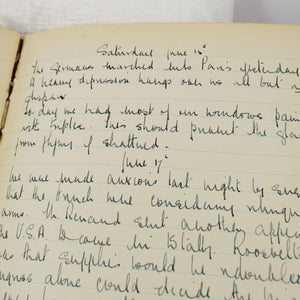

May 15th, 1940: “Today the Dutch Army have laid down their arms. Barely a week ago they were a free people. The Queen, government, Princess Juliana & children are all in England.” Sunday, May 19th: “The war is getting very close now. There is a terrible melee taking place in Sedan and on the French Belgian border — The Germans have penetrated about 60 odd miles into France. They have brought super heavy tanks which have gone through the weakest part of the Maginot Line.” Saturday, June 15th: “The Germans marched into Paris yesterday. A heavy depression has all but NOT despair. To-day we had most of our windows painted with triplex. This should prevent the glass from flying if shattered.”

During this early part of the war True focuses on the watching and waiting in Britain, a time during which she and her fellow citizens were swinging between anxiety and inattention. In September 1939 she writes that “here things are getting rather slack. We feel Hitler cannot bother with us until Poland is finished. Already people are forgetting their gas masks…” Later, “For weeks now we have all been suffering from colds in the head. In fact they have been so persistent that there have been grave doubts in some parts that it could be one of Hitler’s trump cards, or his ‘Secret Weapon’ which he boasts of.” She describes her experience of measures such as the blackout and reports that, “Amongst the things I miss is the sounding of the church clocks in the night”. In December that year she visits London for the first time since the outbreak of war and describes seeing “high in the sky only just visible in the fog & mist… barrage balloons looking rather like fat sausages with large [?] fins. Sandbags everywhere — but apart from the darkened streets & shops there seemed quite as many people as ever.”

But always there is the sense that Germany is getting closer, and True carefully records instances of German fighters being downed in the Firth of Forth and Scapa Flow, as well as the numerous U-boat attacks on ocean liners and Allied battleships.

The unprecedently severe winter of 1939/40 is a frequent subject. On January 25th, 1940 she writes, “This cold has nearly driven us all crazy - frost & snow - burst pipes - water coming through ceilings & general awful discomfort has been our lot for what seems like months”. And she discusses the rationing that had just started. “To-day Father went through the business of procuring our sugar for making homemade marmalade or jam! The fruiterer gives one a signed receipt for so many lbs of Seville oranges (no sugar is allowed for the sweet oranges) this has to be taken to the food control office where a [?] is made out for 1lb of sugar to each 16 of fruit. What a game.”

Other aspects of the diary are both troubling and revealing. In recent decades historians have been at pains to point out that the perception of British self-sacrifice and “stiff upper lip” during the war was only part of a much more complex and morally ambiguous reality, with elements of class, colonialism, and anti-Semitism often at the forefront of events. This is apparent almost immediately in the diary, when on September 3rd, 1939 True reports that, “Since 11 am we have been at war with Germany. All day there has been a flood of evacuees from London — hundreds & hundreds of women & children all housed at the Government’s expense & billeted on private homes here — almost as we were sitting down to lunch we had 2 women & 3 children thrust on us... All the evacuees seem to be Jewish. Why they should choose a small cathedral town to let them loose on beats me. In a very short time both women were grumbling so we tried to get them removed & fortunately were able to do so late in the day to Mrs. Mellow at Vineyard House... We are sorry for these women who have had to break up their homes but they forget our homes are broken up too. Life would have been unbearable had we had to live with that crowd — the women were passable but horribly cheap — the kind who jar horribly”.

Again, in September of the following year she reports that, “The town is again getting flooded with refugees – real refugees this time. People whose houses are in ruins or who have fled the unceasing crash of A.A. guns & explosions. There are some terrible looking Jews about, I would be glad if those people did not send such a feeling of loathing thro’ on. Why is it? I always feel I must hurry by because what I am feeling must be written on my face.”

True was a member of the Women’s Voluntary Services, working as an ambulance driver’s attendant and stationed at the local swimming pool. Many entries record her training sessions, experiences of nights on call, and interactions with other volunteers.

Early in the diary there are multiple reports about conflict over some volunteers being paid, a practice that True disdained, with strong undertones of classism. “…there is a rather [?] air amongst the many so called ‘voluntary’ helpers. I say ‘so called’ because so many of them are being paid... I was called to the Ambulance Station last Friday and stayed there from 7 to 10-20. For this I get nothing however many times I do it after my day’s work. The whole idea of payment is pernicious...”

Voluntary work could be physically difficult but emotionally rewarding. On May 11th, 1941 True describes a practice session. “Saturday I tried my hand at putting out a fire by a stirrup pump. As I was wearing my best slacks & not the usual dungarees, I did not feel too enthusiastic when Mr. Brown invited us to try. However, rolling up my slacks & wearing an old oilskin over my Ambulance coat I waded in. It was great fun really... All went well except for my helmet which fell off… Also we were taken — four at a time into a smoke-filled room — here we had to crawl round the room…I felt sure I was to be the one to cry out for the door to be opened but pride as usual came to the rescue and I crawled out with the others after the longest four or five minutes of my life.”

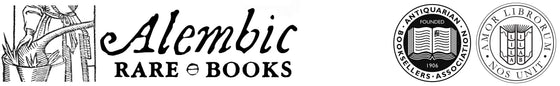

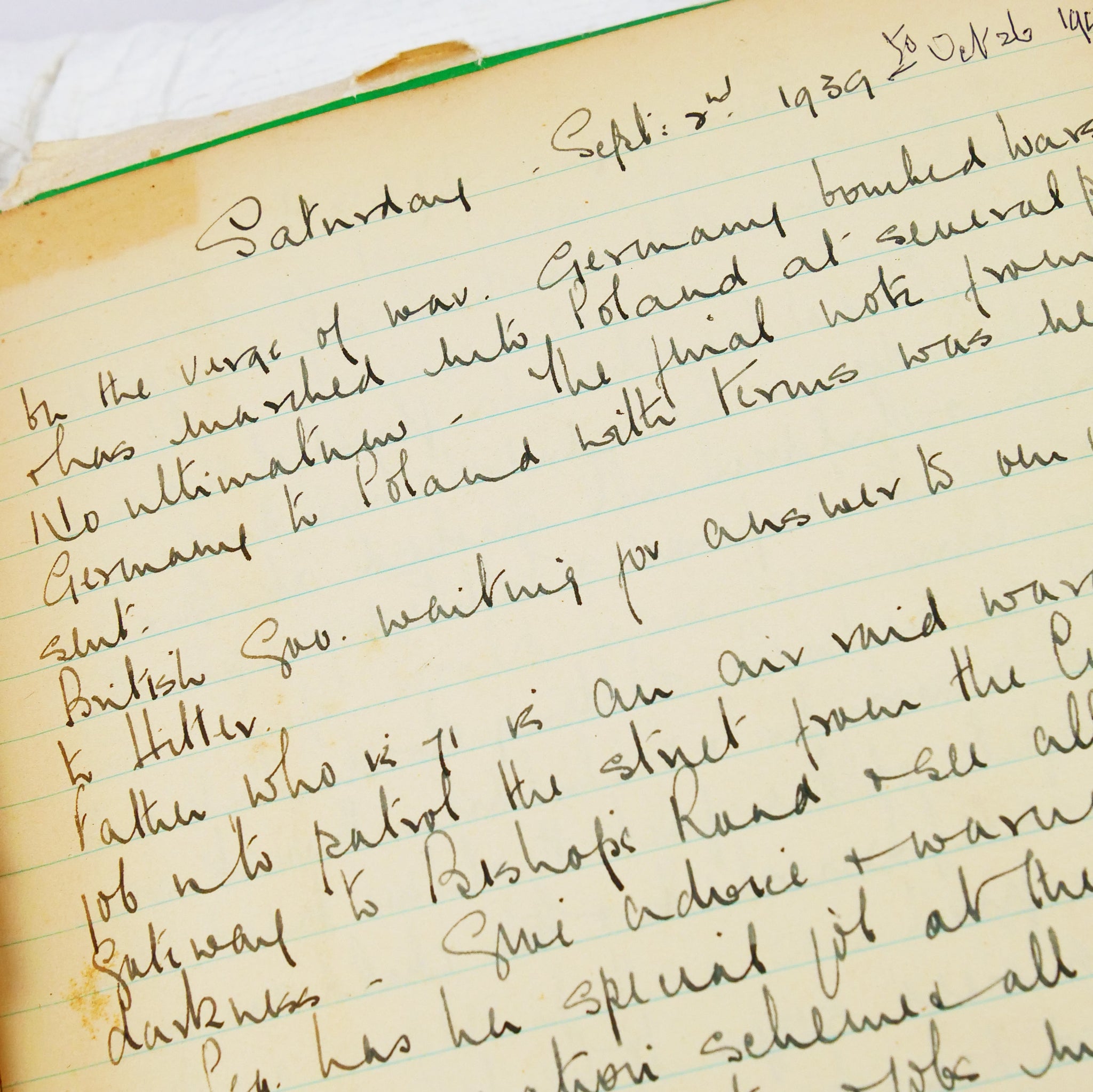

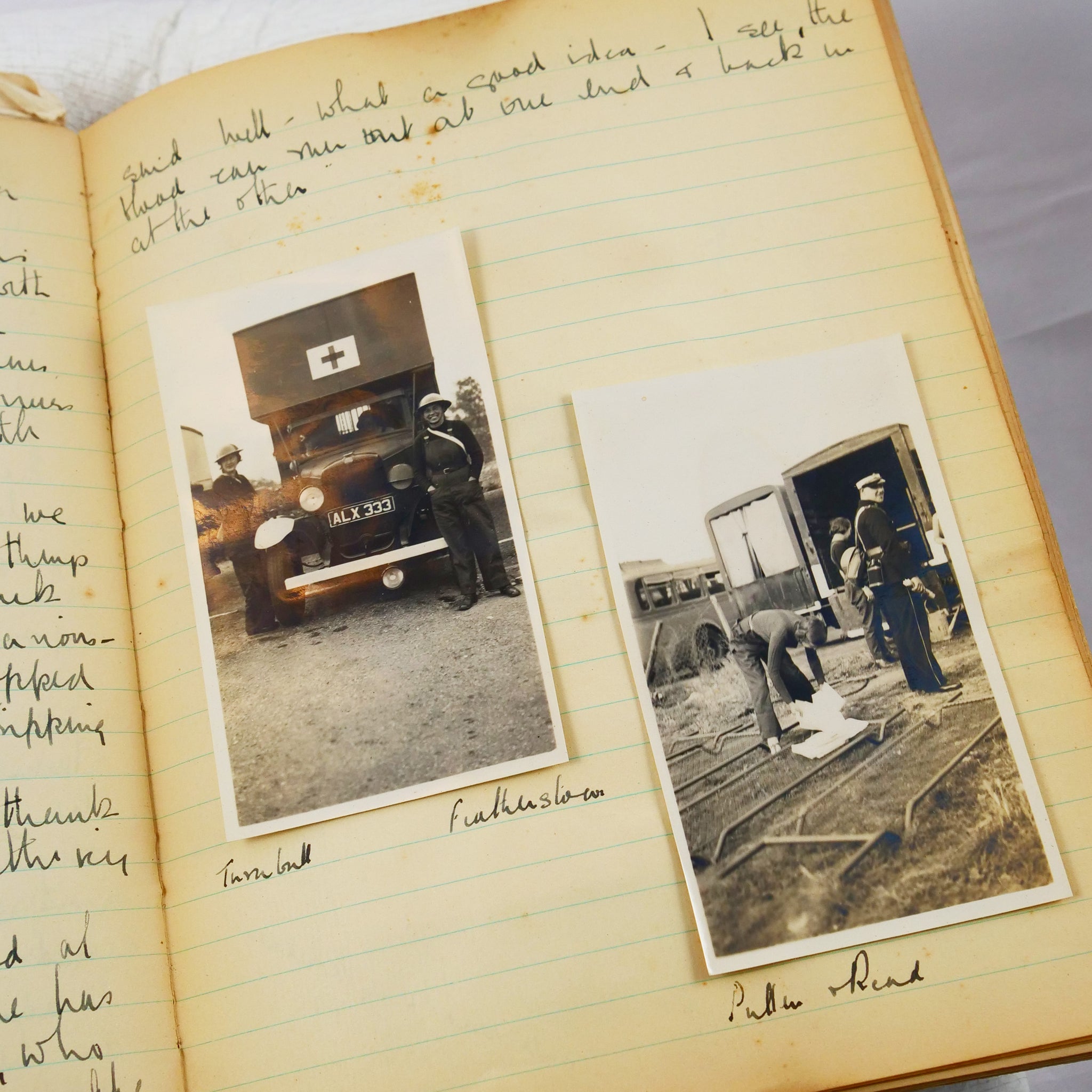

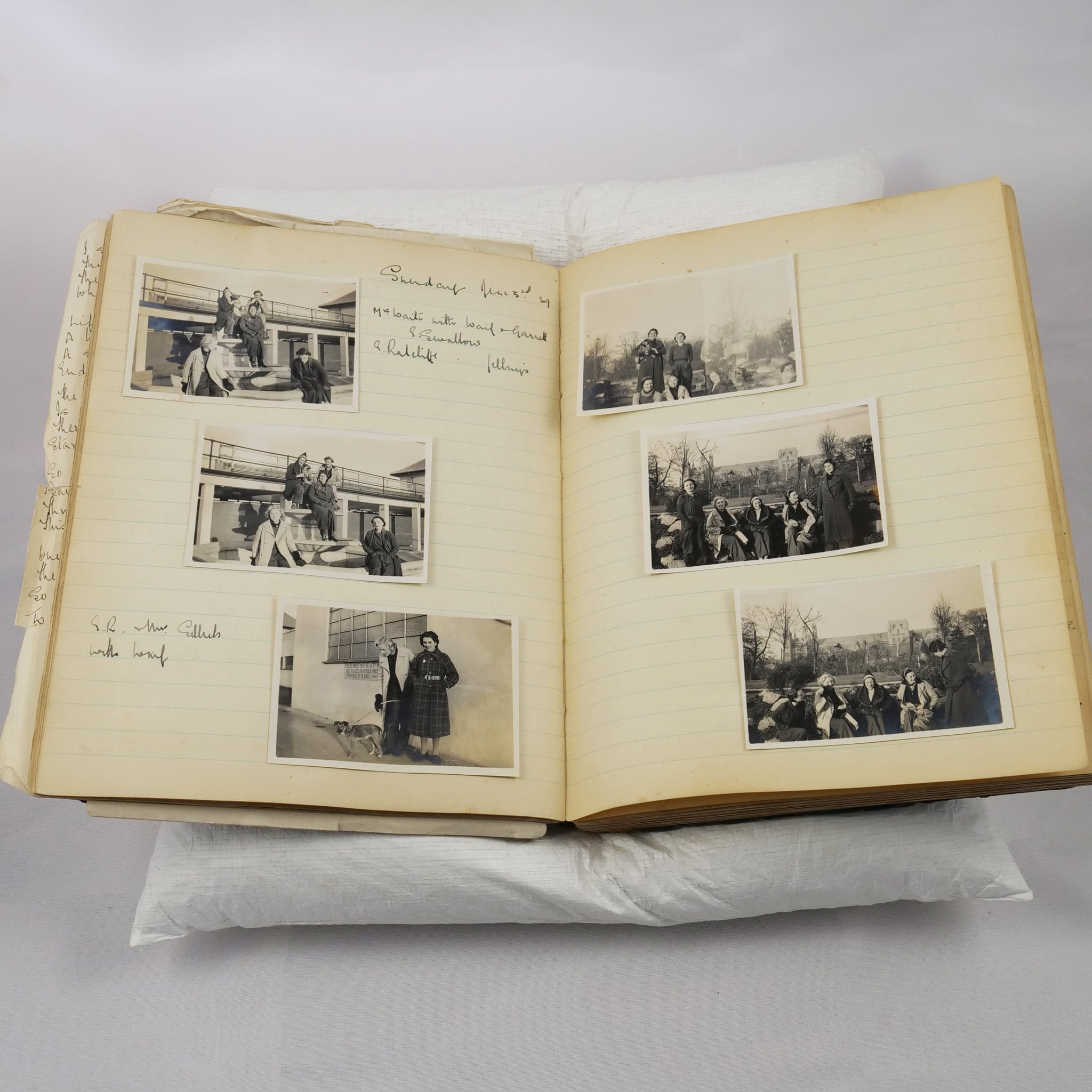

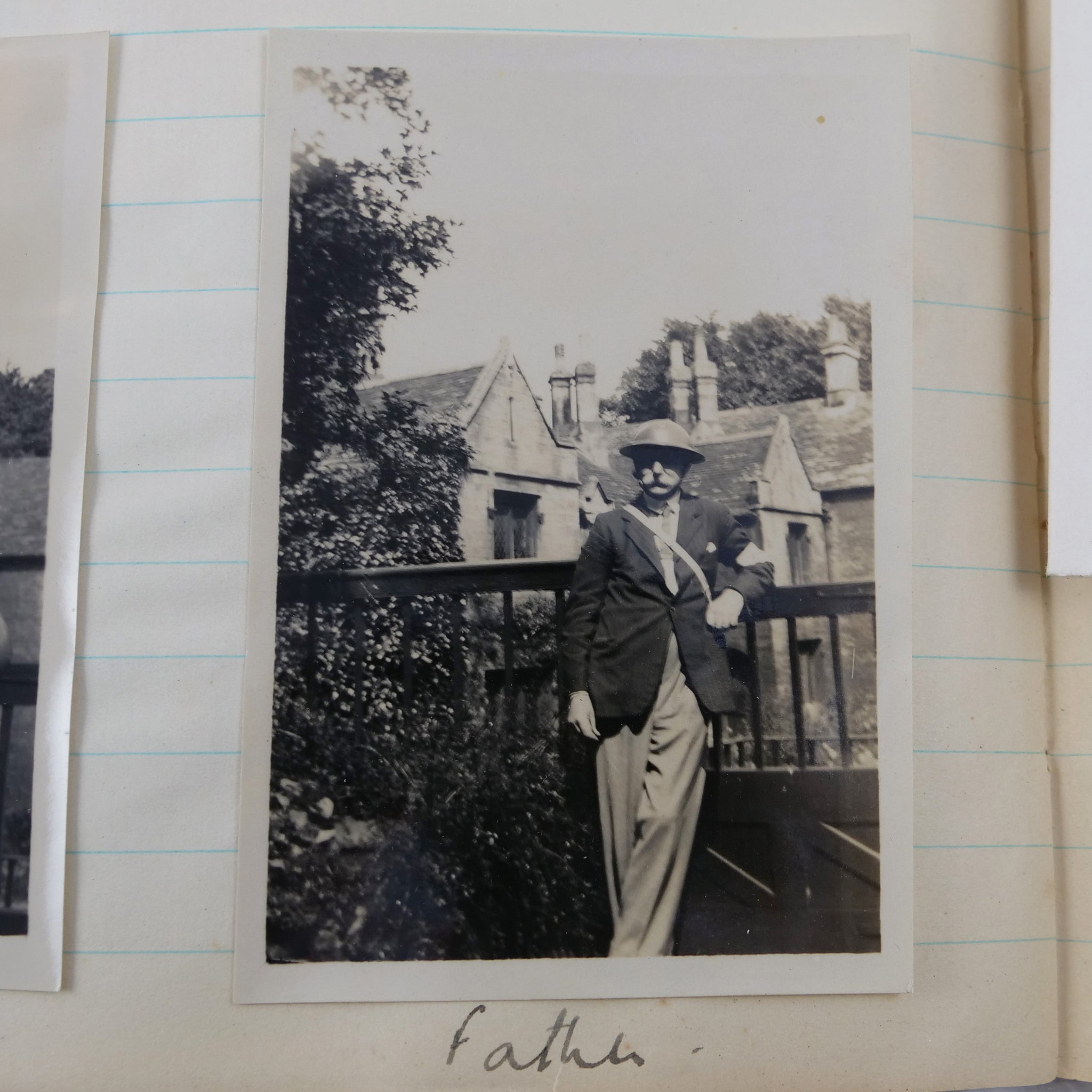

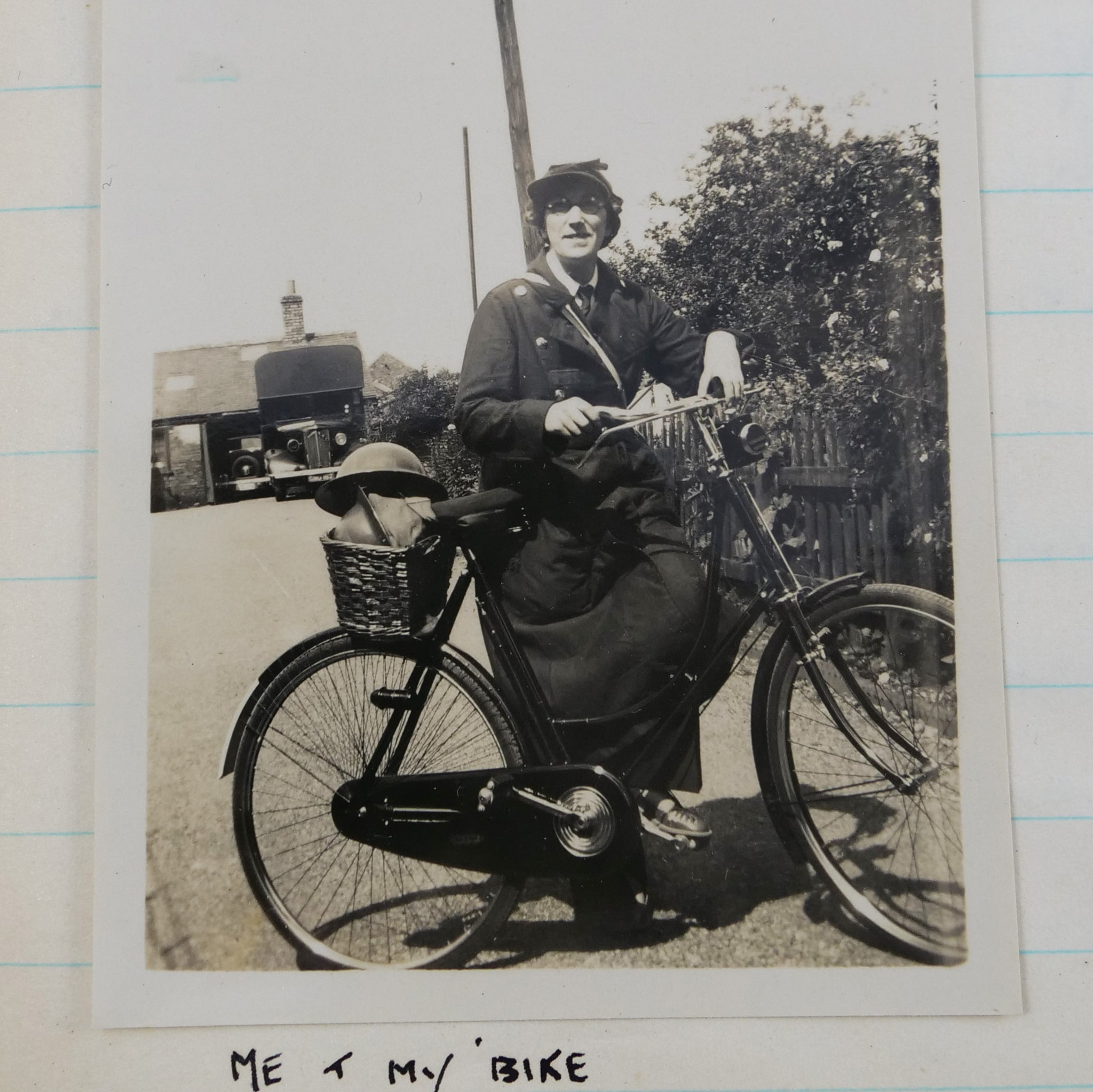

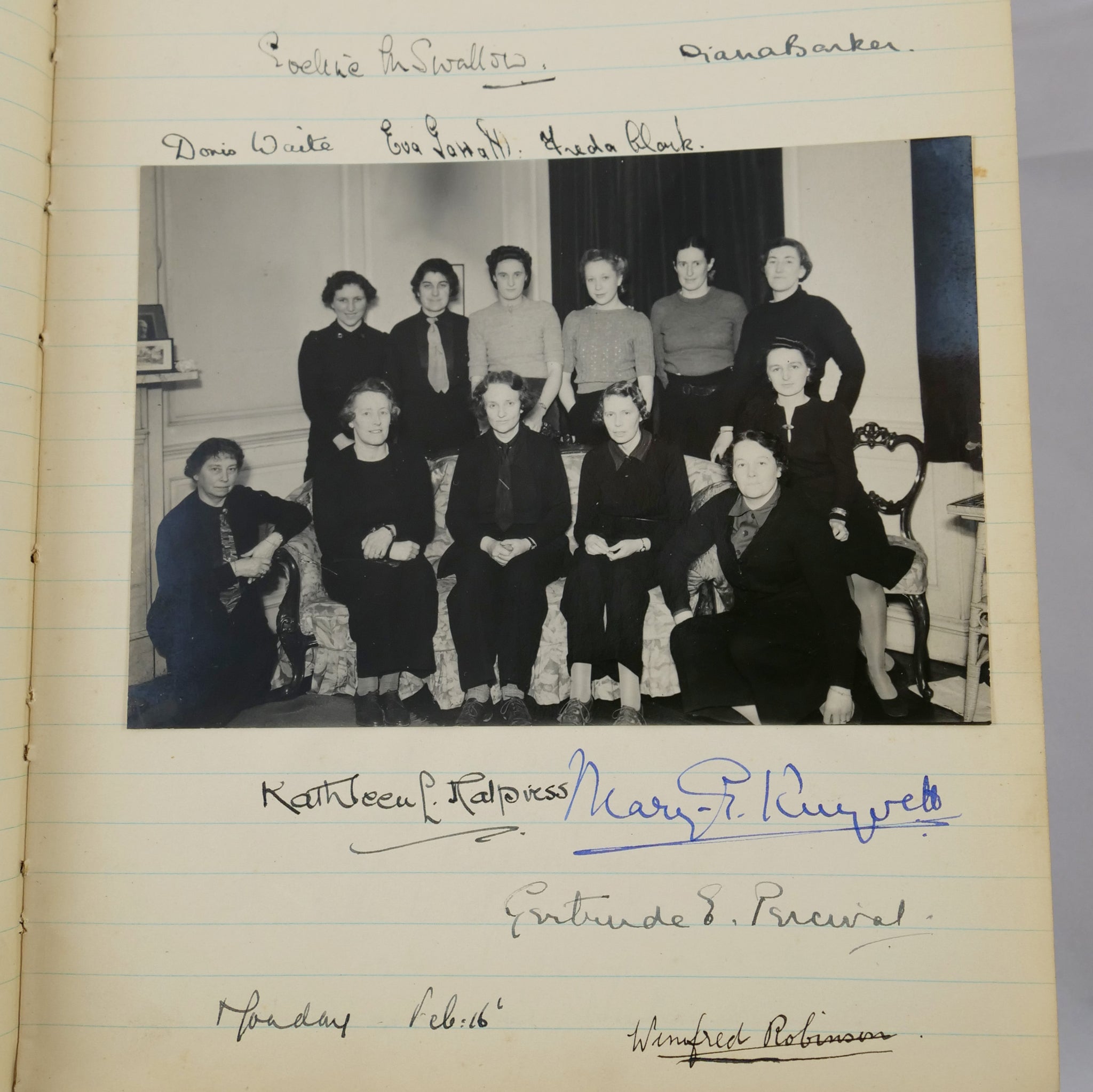

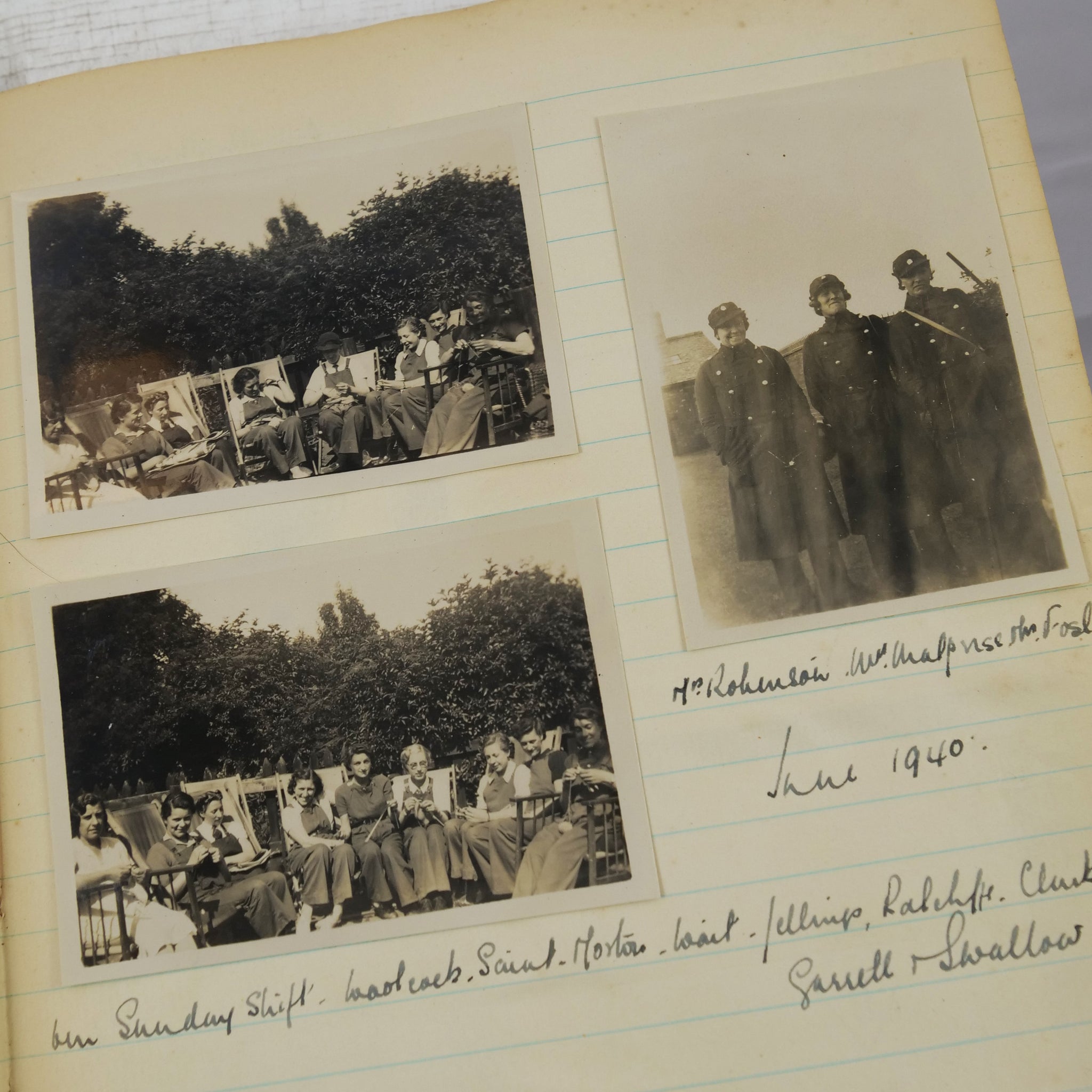

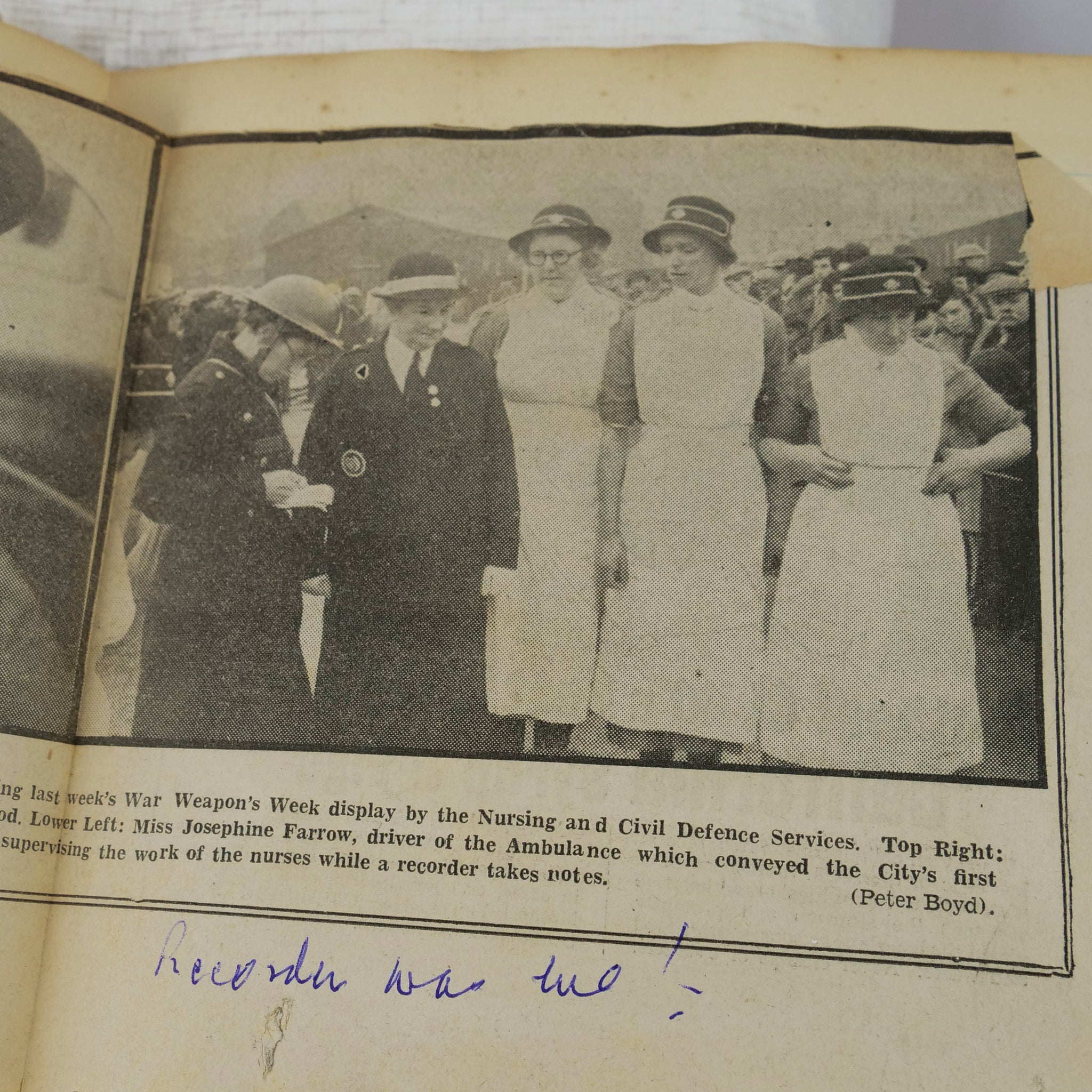

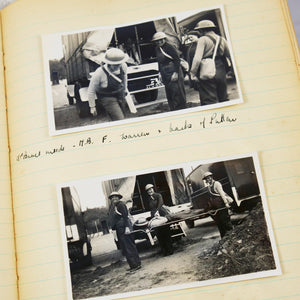

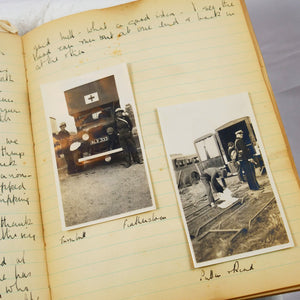

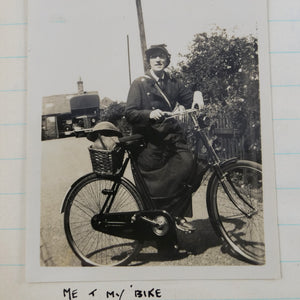

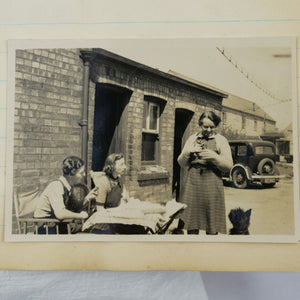

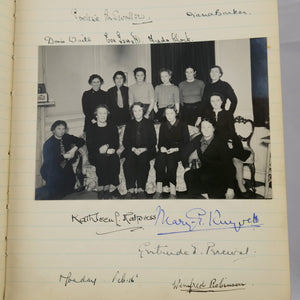

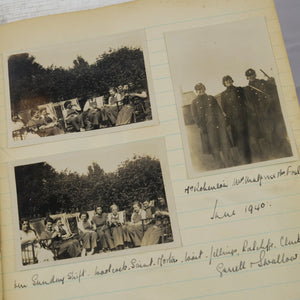

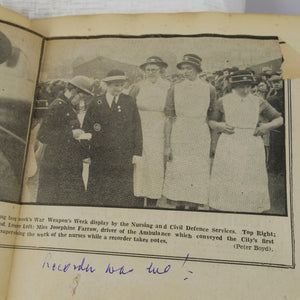

But there are also happier times. True frequently writes about the other women who were good companions during long days and nights, and the socialising they did. Most of these friend and colleagues are mentioned by name and depicted in the numerous photographs pasted-in to the diary (there are also several pages where True has had the other women sign their own names.) Some photos depict the volunteers doing practice exercises such as preparing equipment, cleaning an ambulance, carrying a comrade on a stretcher, and wearing gas masks and emergency oilskins “for mustard gas”. Other images are casual, and show women relaxing together, having tea, holding pets, and posing in front of official vehicles. True usually rode her bicycle to the station, and there are several photos labelled with variations of “Me & my bike”, including one in uniform. There are also images of True’s father — with the handlebar moustache of a different era — in his warden uniform. Additionally, newspaper clippings record the visit of the Marchioness of Reading to the station, as well as a test mobilisation of firefighters in downtown Peterborough (“that’s me talking to Mrs. Fowlis in the ambulance”).

By spring of 1940 the tension reflected in the diary has considerably ramped up, with the German threat coming ever closer to Peterborough. The diary covers the entire period of the Blitz and Battle for Britain, which began that summer, and reports on events throughout the country. On June 19th True describes the anxious wait for the large-scale air raids that the population knew was coming. “A whole week gone & no Battle for England – or rather Britain started yet. Our airmen have put in some marvellous work – this may be one factor. However many hours grace means a lot to us.” And by September she is reporting on the effects of the Blitz, which began on the 7th. Her entry for September 14th, 1940 reads, “London has suffered terribly – & not only London. The Docks have been the chief target but Buckingham Palace received its first & let’s hope last bomb the other night. There have been marvellous tales of courage…”

In early June True describes Peterborough’s first air raid.

Friday June 7th: “This morning about 1-15am? we had our first real air raid warning. It was hot & still and my window was wide open & I suddenly wakened to the fearful din of the air raid siren. I have often said when listening to the practices that we should never hear it but at 1-15 am on a still summer morning it sounded absolutely devilish. After the first paralysing second I leapt out of bed and tried feverishly to get into my battle dress which by great good fortune was handy. Of course the dungarees went on back to front & it seemed hours to me before I set off on my cycle to the ambulance station. At first I was so rattled I had to get off my bike but gradually I calmed down & rode as fast as the darkness would allow — arriving at last to find I was the first of the part timers to appear. I was given a hearty welcome and we then commenced our long wait until the ‘all clear’ went at 3-15. We looked a grim party of women — none of us looking our best, shining noses and hair entirely out of hand. Now and then we heard the uneven drone of the German planes but that thank goodness was all that happened.”

Saturday June 8th: “Last night we had our baptism by fire. To-day the town has a weary look after two practically sleepless nights. About 1-15 again — without any warning a German plane dropped what sounded like three or four bombs in Bridge St., Bishop’s Gardens & the swimming pool!... It is not just a bang - there is a sickening thud which shatters the nerves - At the first moment I felt sick & then began gathering my things in my arms to get downstairs… I must say I listened carefully and sought the sky before venturing forth... What I hate most is thinking of Father on his beat, right in the midst of things. He says that there are several good places to shelter but we are very worried. After another ghastly ride with my heart beating like a sledge hammer & my knees knocking I arrived for the second night in succession at the A.S.”

True seems to have returned to this diary much later in life, as there are a few annotations in a spidery ballpoint pen and some pieces of late-20th century ephemera inserted. On one loose wartime photo of a group of women she writes “How easily one forgets. My Party. This is what I remember of my Party.” The final contemporary entry is dated October 26th, 1941, and ends on the recto of the very last page in the diary. On the verso of that page True has obtained the signatures of a number of her colleagues, and below them, she has later written: “I wish I had got more names to help my memory now on April 12 1992 when the war is over…” This is followed by additional text that is difficult to read because it has been overlaid with white address label stickers, presumably because she or a relative wanted it to remain private.

-

Peterborough, 1939-1941.

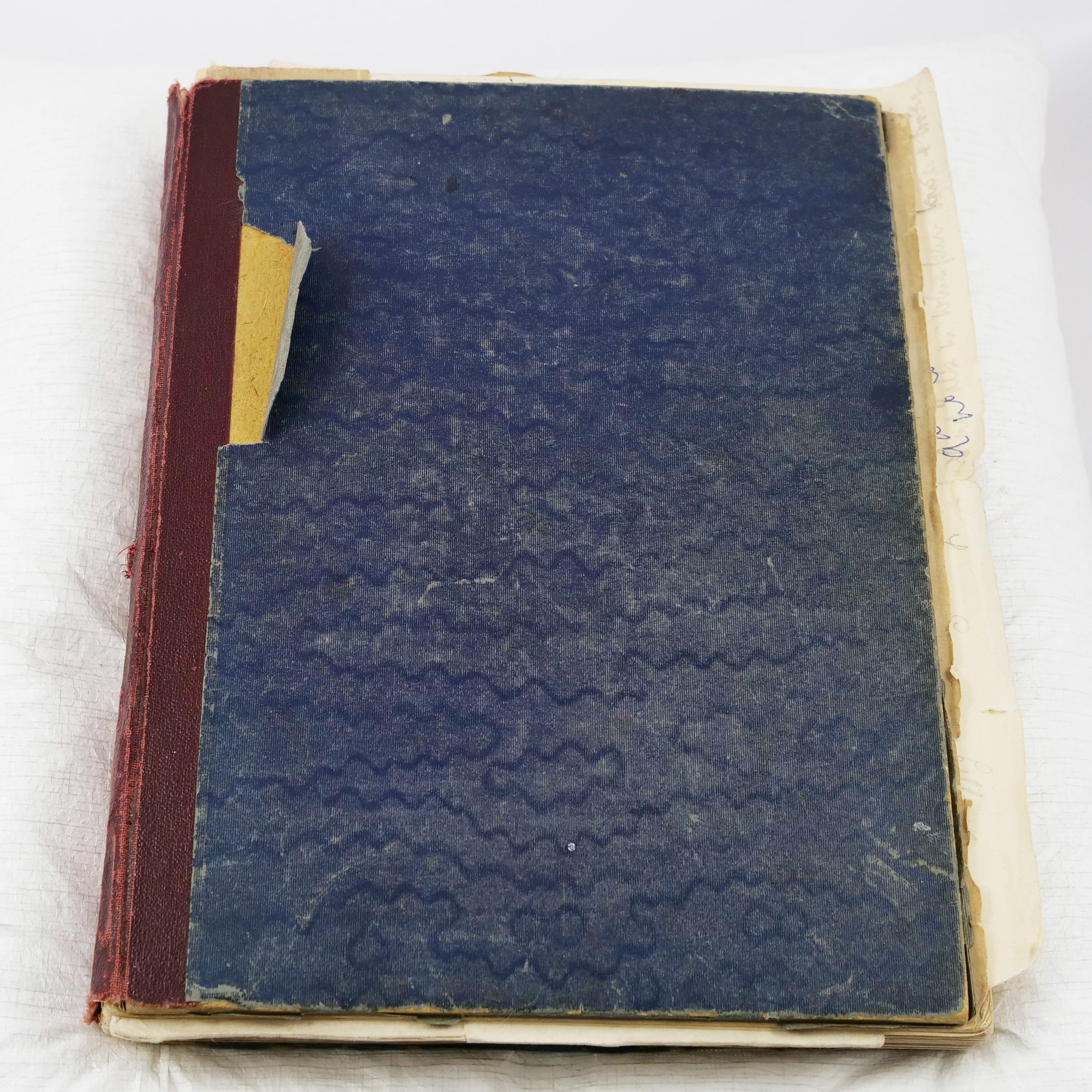

Quarto (230 x 175 mm). Ready-made journal, burgundy pebble-grain cloth backstrip, blue moiré boards, lined paper. Approximately 86 pages of manuscript text, plus loosely inserted manuscript leaves. Ephemera and documents both pasted in and loosely inserted. 65 photographs, primarily 85 x 60 mm with white borders, though a handful are slightly larger and without borders. Most of these are pasted-in, but a handful are loosely inserted. Early in the diary there are glue spots where 4 photos were once attached, and at least two of the loosely inserted prints also have glue on the back. 4 modern white label stickers pasted over some text on the final left, presumably to hide it. Significant wear to the spine and boards, contents shaken, occasional light spotting to contents which are clean and legible. Very good condition.